Observer Name

UAC Staff

Observation Date

Thursday, January 21, 2016

Avalanche Date

Thursday, January 21, 2016

Region

Salt Lake » Big Cottonwood Canyon » Gobblers Knob

Location Name or Route

Gobbler's Knob - Whitesnake

Elevation

10,000'

Aspect

South

Trigger

Skier

Trigger: additional info

Unintentionally Triggered

Avalanche Type

Soft Slab

Avalanche Problem

Persistent Weak Layer

Weak Layer

Facets

Depth

18"

Width

600'

Vertical

1,250'

Caught

2

Carried

2

Buried - Partly

1

Buried - Fully

1

Injured

1

Killed

1

Accident and Rescue Summary

Two skiers, a 50 year old male (Tyson Bradley) working as lead guide and a 49 year old client (Douglas Green), were backcountry skiing in the Mill A drainage of Big Cottonwood Canyon. They were part of a group of 8 containing 3 guides and 5 clients who ascended Gobbler's ridge via Baker pass. They observed a size 2.5 (destructive scale) natural avalanche from the previous day on an east facing slope on Mt. Raymond but no cracking, collapsing or other signs of instability on the day of the accident.

Bradley and one client descended a south facing avalanche path west of and adjacent to the path of the fatal avalanche. After this run the client left the area because he had a meeting in town at 12:30 p.m. They skied the slope without incident while the rest of the group skied a north westerly facing, treed slope known as the “Benign Line.”

After the first run Bradley re-ascended the ridge and approached the top of the run called Whitesnake. He was joined by three others, one of whom was Douglas Green, and an apprentice guide. The third guide and one other client skied the “Benign Line” again.

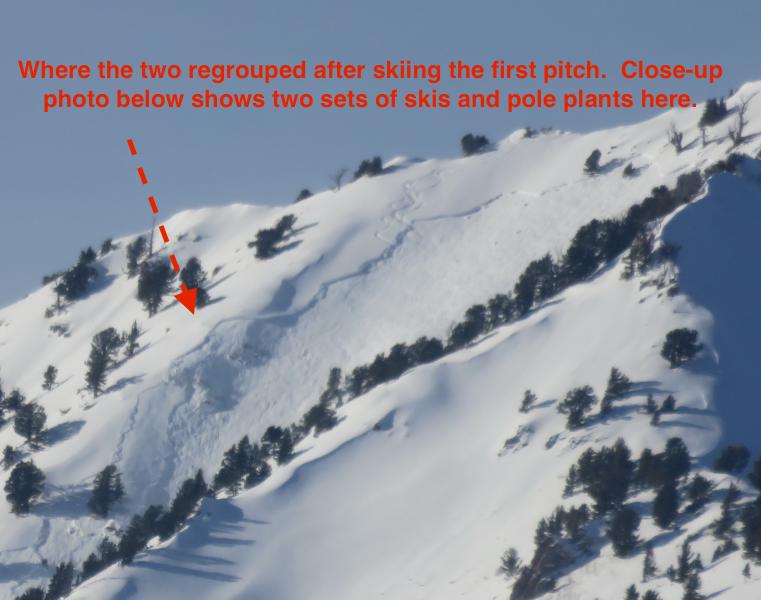

Bradley dropped into the Whitesnake path, made a few ski cuts, and stopped 300' downhill at an island of safety on skier’s right about a foot above and to the side of where the avalanche released (see photo). He directed Green to ski to him. The apprentice guide and the other two clients remained at the top of the run. After regrouping, Bradley began skiing again and directed Green to remain where they had stopped. While skiing the next section, the guide felt the slope collapse (which is the weak layer failing just before the avalanche releases). At the same time he noticed Green had started skiing as well. The apprentice guide and the other two clients remained at the top of the run.

Bradley was caught in the avalanche but continued moving right. He impacted a tree and was pushed upward by the avalanche but not carried downhill. He was partially buried and sustained minor injuries. Green was carried downhill and fully buried. He inflated his avalanche air-bag backpack at some point during the avalanche.

After extricating himself from avalanche debris, Bradley skied down the scoured avalanche path and around an exposed rock band where he triggered a small avalanche. He started a beacon search at the edge of the avalanche debris. After covering several hundred yards of debris, he acquired the Green’s signal. His beacon indicated a distance of 77 meters. At the burial location the smallest distance displayed by his beacon was 0.9 meters. He pinpointed Green’s exact location with an avalanche probe.

Green was fully buried on his side with his head approximately 3 feet deep and his body approximately 4-5 feet. His avalanche airbag was inflated. Maximum debris depth was 15 feet. Bradley dug him out of the debris and began CPR. He could not find a pulse. The apprentice guide and two other skiers arrived about a minute after Bradley began digging. They assisted in the exhausting work of digging Green out of the debris. The avalanche was reported at 14:30 to Alta Central Dispatch by the third guide. A medical helicopter landed and evacuated both the Bradley and Green to a hospital in Salt Lake City where Green was pronounced deceased.

The enormous debris pile snapped aspen trees and covered the terrain trap gully below the avalanche path for hundreds of yards. There was no stauchwall or lower boundary of the avalanche because the slab covering the entire slope released, creating an enormous amount of avalanche debris. The avalanche - estimated at 1-2' deep and 600' wide, pulled down every bit of snow between the starting zone near the ridge at 10,000' and well into the gulley at 9000'. The alpha angle, the angle from the toe of the debris to the crown, was 22 degrees.

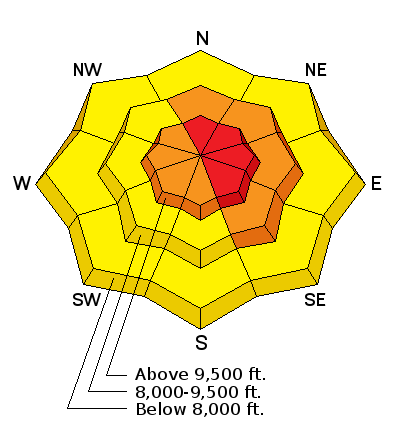

The Utah Avalanche Center rated the avalanche danger in this terrain as Considerable and had issued an Avalanche Warning on January 21, 2016. See danger rose and bottom line below from that day’s advisory.

“There [are] many weak layers and issues that will cause avalanches today. All the red flags are present. Widespread recent avalanche activity both natural and human triggered, recent snow and strong winds, widespread faceted layers in the snowpack, and today will have strong sunshine and temperatures possibly going above freezing. All these factors combine to make very dangerous avalanche conditions and a HIGH avalanche danger.”

The full advisory from that day can be found at:

Terrain Summary

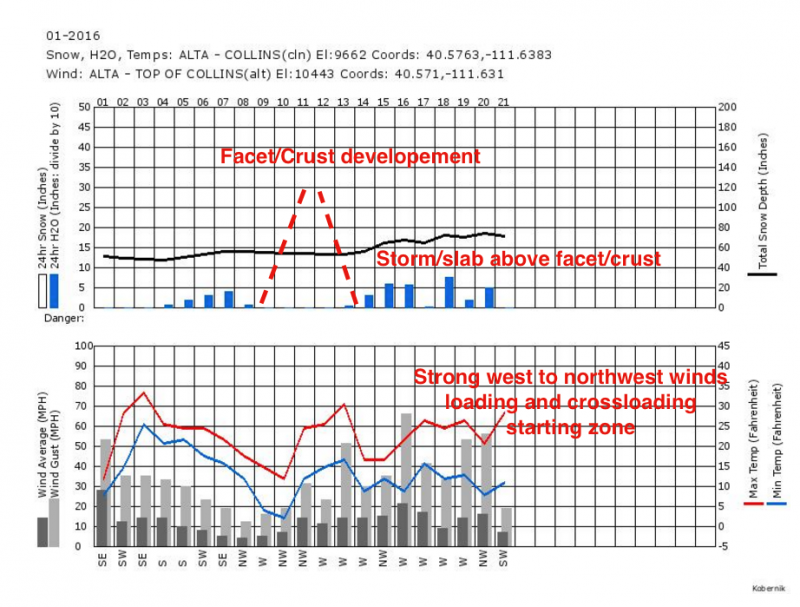

The Whitesnake avalanche path just below the west summit of Gobbler's Knob at 10,246' has a steep starting zone that funnels into a narrow, rocky gully. The starting zone aspects ran from 107 degrees ESE to 215 degrees SSW. The upper starting zone was cross-loaded from strong west to northwest winds in the late evening of January 19 into January 20. Slope angles across the crown were not measured as conditions remained too hazardous to access the fracture line, though the starting zone is estimated at 35-37 degrees. Two adjacent slopes avalanched naturally several days later on

January 24 and

January 27.

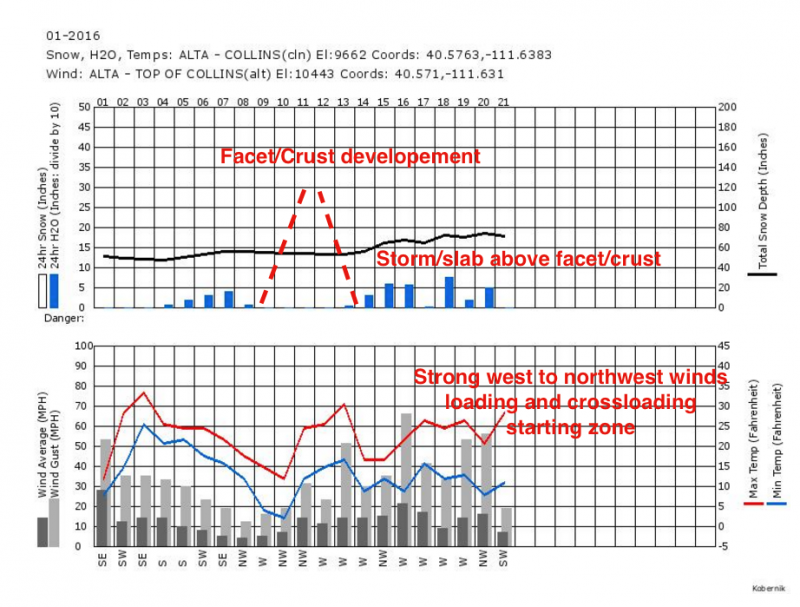

Weather Conditions and History

The weather has been complex this winter. November’s snow was followed by a long, dry spell with only small, intermittent snow storms through early December. Periodic cold temperatures and clear skies faceted the shallow snowpack on shady slopes during this time. A series of storms between December 12th and 25th added several feet of snow to the snow pack and led to a major avalanche cycle.

Weather events became even more complex in January. The New Year was ushered in with a strong southeasterly wind event that scoured and loaded unusual aspects, producing another avalanche cycle. This was followed by small, almost daily storms between January 3rd and 8th. A dry spell between January 9th and 13th, with warm sunny days and clear cold nights, developed near surface facets on shady slopes and created ice crusts on top of faceted snow on solar aspects.

Between January 14th and 20th, snow fell six out of seven days, culminating on January 20th with strong southwest to northwesterly winds, dense heavy snow and an active avalanche cycle. Snow totals from Big Cottonwood and the Park City side ranged from 7” to 11" on the 20th, with storm water equivalents of .65" to 1.04". The Mill D North SNOTEL site had similar SWE numbers.

January 21st had sunny skies and temperatures ranging from near 10 degrees F into the low 20s.

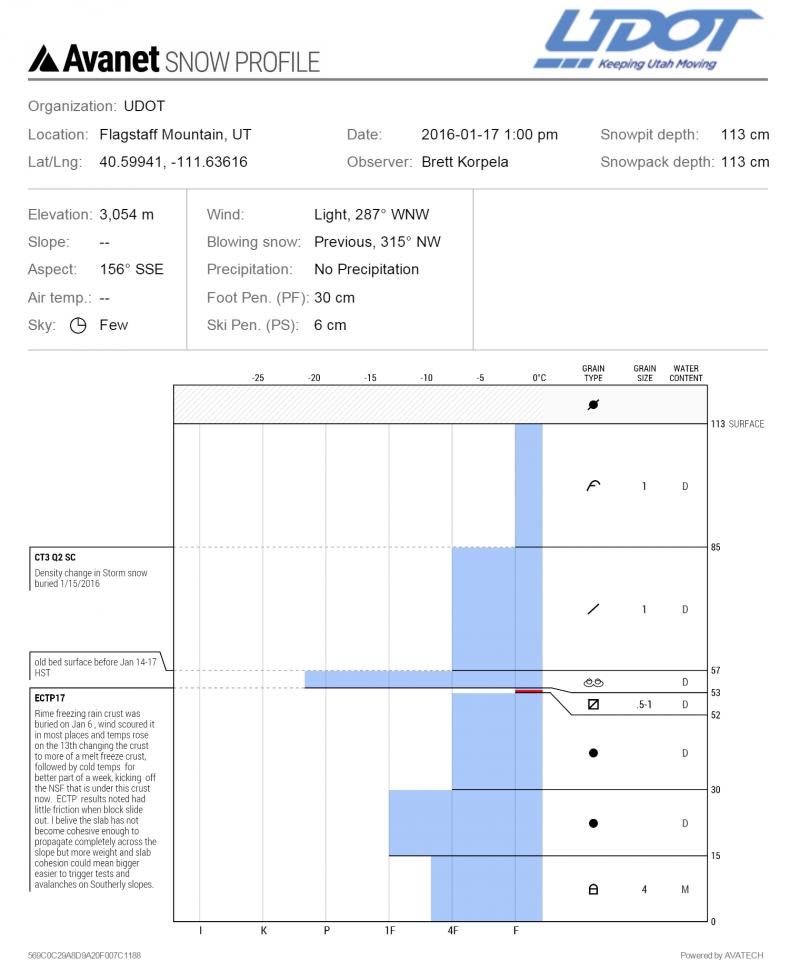

Snow Profile Comments

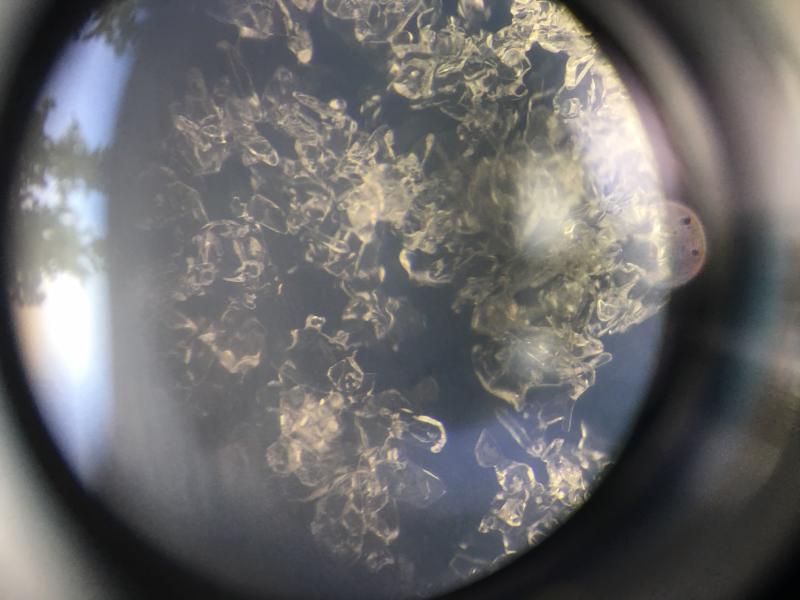

Photo of snow crystals found under an ice crust (UAC Photo).

Access to the avalanche was too dangerous because a large amount of steep snow that did not avalanche was between the safe ridge line and the avalanche fracture line. We examined layering of the snowpack and conducted a number of snow tests adjacent to the crown in representative terrain on a south-southwest facing slope at 9850' and believe that the failure plane was a layer of faceted grains beneath a melt/freeze ice crust. Our findings were similar to snowpack data collected by Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT) personnel on January 17th on similar aspects in Little Cottonwood Canyon (see UDOT Snow Profile from Flagstaff Mountain).

Below is January 17th profile by UDOT LCC and January 22 profile by adjacent to the Whitesnake avalanche path by Hardesty/Meisenheimer.

Comments

Comments

Information in this report was gathered by Utah Avalanche Center (UAC) staff Mark Staples from an interview with Tyson Bradley and by UAC staff members Drew Hardesty and Trent Meisenheimer who visited the site of the avalanche the following day with the third guide, Anna Keeling. This report was prepared by UAC Staff Mark Staples, Drew Hardesty, and Evelyn Lees. Photos provided by UAC, UDOT, and KSL.

Mark Staples, Director

Forest Service Utah Avalanche Center

Video

Coordinates