Forecast for the Ogden Area Mountains

Issued by Dave Kelly on

Thursday morning, April 25, 2024

Thursday morning, April 25, 2024

Thank you for a great season!

Regular avalanche forecasts have ended. We will be issuing intermittent updates through May 1st. This most recent update is from Thursday April 25, 2024.

Regular avalanche forecasts have ended. We will be issuing intermittent updates through May 1st. This most recent update is from Thursday April 25, 2024.

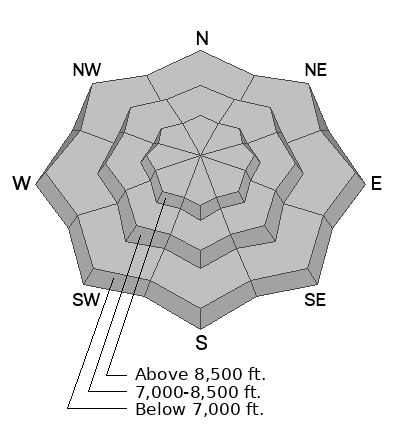

During the spring, there are typically three different avalanche problems:

1. Wet Snow: Wet loose avalanches, wet slab avalanches, and glide avalanches

2. New Snow: New storm snow instability as soft slab avalanches and loose dry avalanches

3. Wind Drifted Snow: Wind slabs; soft or hard drifts of wind-blown snow

Low

Moderate

Considerable

High

Extreme

Learn how to read the forecast here