Observer Name

UAC Staff

Observation Date

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Avalanche Date

Friday, March 7, 2025

Region

Uintas » Hoyt Peak

Location Name or Route

Hoyt Peak/Northeast Bowl

Elevation

9,900'

Aspect

Northeast

Slope Angle

43°

Trigger

Skier

Trigger: additional info

Unintentionally Triggered

Avalanche Type

Hard Slab

Avalanche Problem

Persistent Weak Layer

Weak Layer

Facets

Depth

3.5'

Width

200'

Vertical

600'

Caught

1

Carried

1

Buried - Fully

1

Killed

1

Accident and Rescue Summary

An overview of Hoyt Peak, the accident site, and speculated route that Michael took on March 7, 2025 leading up to the fatal avalanche.

We will never know exactly what Michael’s thought process was on the day of the accident, but what we do know is, Michael was very familiar with the terrain and the route he traveled. He left his house in Marion, Utah, at the base of Hoyt Peak at approximately 8:30 AM. He rode his snow bike, following a summer road to the base of a broad, open, low angle south-facing slope below Hoyt Peak. Michael placed his up track in a safe location and skied two laps on the sunny slope. At 12:10 PM he checked in with his wife via text, indicating all was ok.

We can only speculate about the series of events that occurred after the second run, but we retraced Michael’s third track, which suggests he descended the low-angle, east-facing ramp with the intent of skiing a north-facing run a couple hundred feet from the peak. Investigating the crown and discovering Michael's last turns lead us to believe he entered the slope heading east, intending to ski a much more committing and complex north-facing slope. We saw a very distinct set of ski tracks entering the slope. Given the structure of the snowpack and the characteristics of the avalanche, we speculate Michael had completed several turns on the slope before triggering the avalanche that ultimately caught, carried, buried, and killed him.

Timeline of Rescue & Recovery Efforts

Friday, March 7

At 5:00 PM Friday, March 7, the Summit County Sheriff's Office (SCSO) received a report of an adult male skier who had not returned home as expected. The individual was believed to have been skiing alone in a backcountry area near Hoyt Peak, located northeast of Kamas City.

Search and Rescue (SAR) resources were immediately deployed, and a coordinated search was initiated. During the initial search, SAR teams identified an area with relatively fresh avalanche debris and performed a transceiver search, but no signal was detected. At that time, it was unclear whether the overdue skier had been involved in the avalanche. Due to extremely hazardous conditions, SAR commanders decided to temporarily suspend the search late on March 7, with plans to resume operations at first light on March 8.

A debrief with personnel and Incident Site Commander late Friday evening concluded additional resources were needed to assist with avalanche mitigation, allowing searchers to operate safely and effectively.

Saturday, March 8

On Saturday, March 8, the day began with teams gathering at 7:00 AM at Summit County SAR HQ to plan their response. At 7:40 AM, UAC forecasters Andrew Nassetta and Craig Gordon were flown to the scene by air to assess the area and provide imagery for avalanche mitigation. By 7:55 AM, they returned to the Incident Command (IC).

At 8:00 AM, a DPS helicopter was dispatched for fuel before heading to Canyons Village to pick up a mitigation team. The Canyons Snow Safety team landed at the IC by 9:05 AM to prepare for control work in the accident area.

By 9:35 AM, a combined effort from Summit County Search and Rescue, Wasatch Backcountry Rescue, Canyons Snow Safety, and UAC forecasters reached the accident site at Hoyt Peak. At 10:05 AM, crews began rescue and recovery operations, working through debris with the help of two dog teams.

At 10:45 AM, Dog 1 indicated a signal in the avalanche debris, and a probe strike uncovered a ski. Just two minutes later, at 10:47 AM, Dog 1 indicated another signal 10 feet upslope, with blood found on the snow. By 10:49 AM, a positive probe strike confirmed a burial at a depth of 50-80 cm.

Tragically, the overdue skier was found deceased. It was determined that the individual, 51-year-old Michael Janulaitis from Marion, Utah, had been caught in the avalanche. Michael was not wearing an avalanche transceiver. We'd like to thank Summit County Sheriff and SAR teams, the Utah Department of Public Safety, Park City Mountain Resort and Canyons Village Snow Safety and Ski Patrol teams, and Wasatch Backcountry Rescue for their hard work recovering Micheal and returning him to his family.

Terrain Summary

Hoyt Peak is located on the west side of the Uinta Mountians, nestled south of Weber Canyon and north of the Mirror Lake Corridor. Hoyt Peak's elevation is 10,200' and it stands out above the rest of the surrounding peaks in the periphery of the range. The slope where the fatal avalanche occurred is a steep, northeast slope that is full of small cliff's, rocks and trees with a starting zone that averages 40-45 degrees in steepness. Although the slope lacks terrain traps, there is no shortage of consequential objects to encounter on the ride down. The runout is mainly low-angle. Well-spaced old timber is found near the terminus of the avalanche debris.

Measuring 43 degrees in slope steepness, this is unforgiving, complicated, treed terrain with several mid-slope breakovers adding to the complexity.

Looking down from mid-slope at powder-blasted trees that indicate the velocity and severity of the slide.

Looking up from the debris of the avalanche with rescue teams near the burial site.

Weather Conditions and History

Late October and early November storms delivered shallow coats of early winter snow to the western Uintas. A substantial shot of Thanksgiving moisture provided some substance and created enough base to kick off the winter season. However, the moisture tap dried out as the jet stream shifted far to the north of the Uinta region. This set the stage for a weak snowpack and basal faceting, along with a few early season avalanches. However, the blueprint for a structurally challenged snowpack was written. A powerful holiday storm stacked up a couple of feet of dense, heavy snow, producing a widespread avalanche cycle as winter returned from its hiatus during the Christmas and New Year’s holidays.

Storm systems lined up on the West Coast and looked promising going into the New Year. However, those hopes faded as most of the energy evaporated once they came onshore. Dribs and drabs of moisture would offer the remnants of once robust storm systems, but they lacked substantial snow water equivalent (SWE), which would help the snowpack gain strength. Unusually cold mid-January temperatures combined with a two-week dry spell, set the stage for another round of faceting.

Skier triggered avalanches on February 8th near Hoyt Peak, breaking to weak January snow.

Early February was marked with a warm, wet, and very windy storm, but little snow accumulated near Hoyt Peak until February 7 when the Redden Mine SNOTEL recorded 4” of snow and .60 SWE. Near Hoyt Peak, storm totals are slightly more… 6” snow with .80” SWE. During the height of the storm, winds blowing from the south and southwest cranked in the 40s mph and blasted into the 70s near the high ridges. Post-frontal cold air delivers 4” of low-density snow to wrap up the storm on the February 8.

Clear, cold weather settles in from the February 8 - 13, though a multi-day storm was on the horizon, slated to settle into the region beginning mid-month. An Avalanche Warning was issued on February 14, and the Valentine’s storm cycle churned away for 48 hours, stacking up 15” of snow and 1.7” SWE at Redden. Higher in the drainage and closer to Hoyt Peak, 20” of snow with 2.2” SWE piles up. Nearby ridgelines experience steady winds blowing from the west and southwest 30-50 mph throughout the storm.

Four inches of low-density snow falls on February 20, but the storm track shifts north once again, and February wraps up with high pressure and warming temperatures.

Minor storminess produces a couple of inches of snow for the first week of March, but that’s the precursor to a larger, more energetic system that slid into the Uinta zone on March 4 - 7. It's not quite as energetic as the Valentine’s cycle, but the early March system heaps up nearly 24” of snow with 1.9” SWE. Moderate southwest winds blow in the 20s and 30s for almost nine hours. As the storm taps into cold, unstable air, winds died down and turned northwest. The storm is right-side-up, meaning the dense snow is at the bottom and lighter on top, and the riding conditions are all-time.

Under mostly cloudy skies, a few snow showers linger on the morning of Friday, March 7. Temperatures are in the teens, and westerly winds blow 10-20 mph near the high ridgelines.

February started off slow, with two small storms delivering barely an inch of SWE. However, the mid-month Valentine's storm got things rolling with strong winds and two distinct impulses totaling 4.1" of SWE and nearly 36" of dense heavy snow. Above is a data run from nearby Redden Mine (8,540') sno-tel site.

Normally void of snow, Windy Peak weather station shown here on the tail end of the moisture-laden Valentine's storm, plastered with dense snow.

Snow Profile Comments

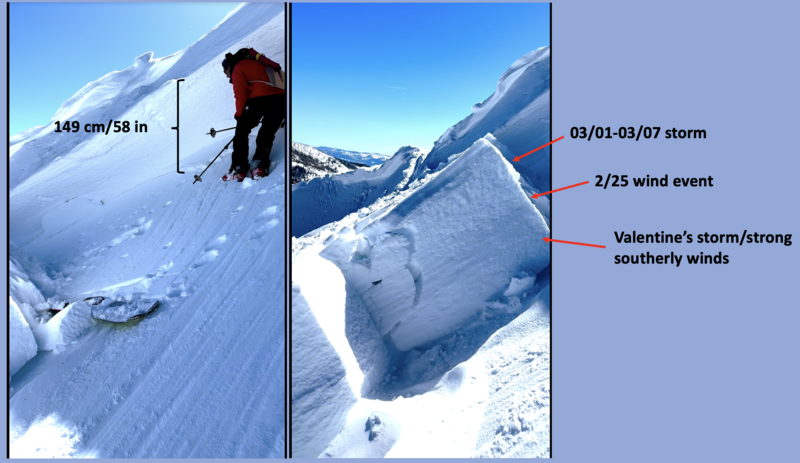

The Western Uinta’s are known for their shallow, weak and continental-esque snowpack, the 2024-2025 season is no different. At the time of the accident, the upper snowpack consists of 1’ of storm snow resting on a dense, strong slab on top of a crust with a thin layer of facets beneath it. The lower pack has weak snow from a dry period in January, with some lingering hard snow below, and the base of the snowpack consists of weak snow from the early season.

Western Uinta avalanche forecast for Friday March 7th.

Images above are near the skiers right flank of the avalanche.

Forecaster Andy Nassetta identifies a thin layer of faceted snow near the early February dust later.

Comments

Profile represents the most accessible, yet deepest portion of the crown.

Comments

Comments

Comments

Forecaster Comments and Thoughts -

It was not unusual for Michael Janulaitis to snow-bike and ski solo. But like all lone mountaineers, this manner of travel left him vulnerable to the slightest gear malfunction, injury, or other mishap… let alone triggering a large avalanche with no one to assist in a rescue.

The route, the terrain, the local weather and snowpack complexities, and the mode of travel were all very familiar to Michael. However, it is probably this familiarity that led to a feeling of comfort. Unfortunately, with no one to interview, there are lots of gaps and many unanswered questions. We can only speculate on Michael’s decision-making and objectives by retracing his tracks and offering our evidence.

We are deeply saddened by this tragedy. We thoroughly investigate avalanche accidents and share our findings to hopefully learn more about the contributory factors leading up to the incident. Our ultimate goal is to offer transparent findings, share those thoughts with our community, and help prevent another backcountry avalanche accident.

Coordinates